Sharing Our StoriesWilliam F. Perdue

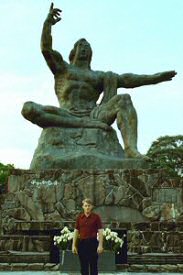

Page 2: June 22-23, 1975 Late in the afternoon, another train rolled into the Nagasaki station. Thirty years after the bomb, things had changed dramatically. This time, the green fields and hills gave way to a thriving city with homes, businesses, schools, and buildings of all kinds were everywhere. The streets teamed with activity as cars, bicycles, and people rushed along their way. There was nothing that would have led you to believe it had ever suffered the level of destruction it had in 1945. Now, it looked like any other port city in Japan. My trip to Nagasaki came about early in my 21-year career in the Navy. Our ship was visiting Beppu, Japan – a popular resort city on the northeast coast of Kyushu. Since Nagasaki is located on the same island, I decided take a couple of days leave and set out to find my way to there. wanted to make the pilgrimage as a sort of surrogate for my dad… to contrast with his experience of nearly thirty years earlier. After a seven-hour trip, I was excited to finally be there. I found myself wandering around just enjoying the adventure and taking in the atmosphere. Too late in the day to really see much, I checked into the New Nagasaki Hotel and made my plans for the following day. Rising early, I set out on a 2-km walk to my first objective: Peace Park, which had been built around the atomic bomb epicenter. Fat Man had exploded 500 meters above the black stone monolith that now marks the spot. The park was strikingly beautiful – broad walkways lined with a profusion of plant and colorful flowers wound around various statues and memorials. One of the most interesting was Peace Statue. This bronze statue, 10 meters high and sitting on a 4-meter base, was erected in 1955, according to a translation of the inscription, “as an expression of sincere desire of the citizens of Nagasaki for everlasting peace in the world.” Park literature further describes the statue’s symbolism. The right hand points to the threat of nuclear weapons, while the left hand symbolizes peace, and the face expresses prayerfulness in memory of those who were killed. All and all, it is not a thing of great beauty. Elsewhere in the park, there was a large vault that contains the unclaimed skeletal remains of atomic bomb victims collected from Nagasaki City and nearby towns. Around another bend, the pathway is bordered by the remains of a wall that surrounded a prison that was destroyed in the blast. The ruins of Urakami Cathedral (which had been the largest church in Japan) were moved to the park as a reminder of the destruction. Just outside of the park, a pair of giant camphor trees stands near the Sanno Shrine.The upper branches of the huge trees were broken off by the force of the bomb, after which they lost all their leaves for a time and were thought to have died. However, new leaves sprouted and they continued to grow. The trees were designated as "living memorials" by the City of Nagasaki. A short walk to the edge of the park brought me to the atomic bomb museum (officially, the Nagasaki International Cultural Hall). Visiting this building was by no means a pleasant experience, but it was certainly a very important part of experiencing Nagasaki. I was disappointed that photography was prohibited in the museum. The museum is clearly designed to impress upon visitors the horrifying effects of the atomic bomb. (Not surprisingly, the people of Nagasaki were VERY anti-nuclear.) As I entered the building, I found myself in a large, open foyer with a ramp that spiraled upward toward a glass dome. Some have suggested that this is designed to resemble the bomb’s mushroom cloud. The first exhibits were pictures of Nagasaki before the bomb. As I walked along, I was assaulted by the ominous, loud ticking of a clock. The exhibits progressed through events leading up to the bombing, the devastation afterward, reconstruction efforts, and continued with displays of a decidedly antiwar, antinuclear slant. Numerous artifacts graphically depicted the destructiveness of the bomb. There was a clock on display which had stopped at 11:02am (precisely the time of the explosion). All kinds of personal effects were on display: mangled glasses, charred shoes, and clothing singed on one side, untouched on the other. I saw the bones of someone’s hand encased in a clump of melted glass. All kinds of metal objects had been melted down. There were coins fused together. The pictures of victims were particularly graphic. One was of a dead mother and her baby… another of a teenager whose face had been hideously burned. Perhaps the most haunting image wasn’t a photograph at all. A section of a building was on display. The explosion had caught a man in mid-step. Acting as shield, his incinerated body left only a ghostly shadow etched onto the wall. It had been a sobering experience, but I was ready for more cheerful sights as I finally walked out of the museum into the bright sunlight. Protected by the hills surrounding the city, many historical sights in Nagasaki were protected from the atomic explosion. Among them was the oldest church in Japan, Oura Cathedral. The cathedral was built by French missionaries in 1864 originally for the exclusive use of Nagasaki’s foreign community. The Japanese were forbidden from practicing Christianity until 1872. On a hill a few miles removed from the bomb epicenter, the Grover Mansion had survived untouched. This was the home of Thomas Glover, a Scotsman who built the shipyards in Nagasaki which were the target of the bomb. Built in 1863, the home is the oldest Western-style house in Japan and was romanticized as the home of Madame Butterfly (in Puccini’s opera). From its perch, I had a panoramic view across Nagasaki wan (harbor) and out toward the area that had been leveled thirty years before. As I boarded the train to head back to Beppu and my ship, I was very pleased with my trip to Nagasaki. While I, like my father, have no regrets that the United Stated used the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, having the opportunity to visit the museum gave me a feel for the devastation wrought by nuclear weapons and a healthy respect for their deterrent power. I was also glad to see that, like the Sanno Shrine camphor trees, a vibrant city had risen from the ashes. I think my dad was happy to see the pictures of the new Nagasaki and hear about the changes as well… perhaps bringing some closure to his experience of thirty years before. |

|

|||||