STORIES

Kenneth Anderson

A.J. Ball

Bill Briggs

Regis Carr

James E. Carter

Gregg F. Corcoran

Larry Davenport

Mary DeAngelis

Mae Green

Roger A. Gregg

Bobby G. Grider

Josh J. Grider

Joseph Gross

Charles W. Hackett

Tom Haupt

Charles C. Hinson

Jay Luster

C.E. Moyer

Dennis M. Murton

Dennis Murton, Jr.

Chuck Newton

Bobby Onuska

Jerome Parson

William F. Perdue

Terry A. Roe

Sandra S. Simpson

Connie Rubin Smith

Jutta Spencer

Dale Stevens

Stephan Stocker

Clint Summers

Timothy Tuohy

Jack Zist

Willam F. Perdue

Willam F. Perdue

Manager Planning Systems

Norfolk

Arctic Expedition

Autumn 1981

The ship lurched and shuddered as 35 foot waves crashed broadside into the beam. Once again the main engines had shut down, leaving the USCGC Northwind wallowing helplessly in the unforgiving storm. As much as possible, the captain tried to run with the seas. But this was no ordinary following sea. Occasionally, the already towering seas would phase just right, and a monstrous 50 or 60 foot wave would barrel down on us, looking as if it were going to swallow the ship whole. As the stern lifted high on the crest of the wave, the giant screw would break free of the water, spinning uselessly in the air. With the sudden loss of the water’s resistance, the engines would begin to over-speed and automatically shut down. Without power, the ship helplessly turned and ended up parallel to the seas; the waves free to sweep across the decks and toss the ship about like a toy. For those of us aboard, there was nothing to do but hang on through the 60+ degree rolls as the ship’s engineers struggled to restart the big diesel engines.

We were crossing the Greenland Sea, southbound for Scotland after a seven week oceanographic expedition in the artic ice. For two days, the mid-November storm generated hurricane force winds and mountainous seas that pounded the icebreaker and made life miserable onboard. Sleep was out of the question. Cooking was impossible (unless you count sandwiches of “mystery meat” on dry, stale bread). The officers’ wardroom (the lounge and dining area) had been rendered uninhabitable (and downright dangerous). A large, four-burner Bunn coffee machine, along with the table to which it was bolted, had torn free from its welds on the deck and bulkhead. Now a 50-lb wrecking ball, it roamed freely about bashing everything – television, VCR, dishes, and furniture. It owned the space and its ruins, putting quite a punctuation mark on an adventure that had begun a year earlier.

The Expedition FormsRiding a Coast Guard icebreaker in the arctic was certainly an unusual assignment for a Navy lieutenant. But then again, my “job” for the previous two years had been to attend the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, California and earn a Master of Science degree in meteorology and oceanography. The culminating requirement for the degree was to produce a thesis. Generally, this is a long, tedious, and sometimes boring task of analyzing piles of some professor’s data so that he can use your work to publish a journal article in his name. Fortunately, one of my professors, Dr. Robert Bourke, rescued me from that fate by offering a rare opportunity to do something really different. He was forming an expedition to do hands-on research in the arctic and wanted me to join the team. I couldn’t believe my good fortune! (Of course, I had little idea what I was getting myself into, but the sense of adventure was too great to pass up.) My thesis would be based on the initial analysis of our investigations using the data that I actually helped to gather.

It was the opportunity of a lifetime… a chance to go were very few have ventured before and follow the footsteps of great arctic explorers like Admiral Robert E. Peary, the first to reach the North Pole or another admiral, Richard E. Byrd, the first to fly over the pole. Back in reality, our mission was somewhat less grand and glorious. Headed by our sponsor, Dr. Alan Beale of the Arctic Submarine Laboratory, our team of four scientists (I loosely include myself in this group) and two technicians was to conduct oceanographic research along what is know as the East Greenland Polar Front (an underwater thermal boundary that runs under the ice from the Arctic Ocean southward off the east coast of Greenland). Our investigations would take place during the late autumn time period when no previous studies had been attempted. Increasingly hostile weather conditions, thickening ice and constant darkness presented unique challenges to effective research.

Steaming Into the NightOur expedition started calmly enough. Facing a stiff, northerly breeze, we set sail under an azure blue sky from Reykjavik, Iceland in early October 1981. At this time of year, the sun, even at its zenith, never managed to rise more that twenty or so degrees above the horizon. As we left the rugged coastline of Iceland behind, we knew we would see less and less of that friendly orb as we traveled steadily north of the Arctic Circle. Eventually, sunrise and sunset would become one, and then nothing would be left but the long arctic night.

Once our equipment was unpacked and tested, there was little to do at first but enjoy the crisp, clean air as the ship transited the choppy seas. The ride on the round bottomed icebreaker was less than smooth. (No surprise since the ship rocked incessantly even at the pier.) Soon, however, the seas would calm as we encountered “grease ice”. This was first stage of forming sea ice. Here, the waves were dampened by the thin film of freezing seawater which took on the silky sheen of a giant oil slick. As we continued, the ice began to form into clumps or “pancakes”. The pancakes continued to grow and thicken. Eventually, they bunched together and formed the solid sheet of first year ice. Our destination carried us far beyond this marginal ice zone and deep into multi-year ice several feet thick. Eventually, our forward progress was slowed as the thickening ice forced the icebreaker into “back and ram” technique. The Northwind would back down in the channel it had just created and then steam forward, slamming the heavily reinforced bow (over three feet of solid steel at its thickest) of the ship up onto the surface of the ice, the weight of the ship breaking through the ice.

Our work soon began in earnest. We split the group into two teams that would work in 12-hour shifts for the next six weeks. I quickly learned that there was little “adventure” involved in gathering the data. At selected points, the ship would stop and we would lower our instrument package (a conductivity-temperature-depth (CTD) recorder) through open areas in the ice to continuously measure the conductivity and temperature of the water as the devise descended into the depths. With the data safely stored on tape, the Northwind would crunch its way slowly through the ice to our next planned location and the whole process would be repeated. Between CTD casts, we would process the data using what would now be considered a very crude desktop computer (a Hewlett-Packard 9835). Conductivity readings were converted to salinity values and, along with temperatures, plotted against depth. We would later analyze a series of profiles to give us a picture of the underwater structure. As I said, there was not much excitement gathering data.

“Furry Visitors” & Other DiversionsOff-duty time offered little in the way of excitement either. When we were not sleeping, we idled away the hours reading, watching movies, playing cards, or just watching the ship battle its way through the thickening ice.

At least for the early days of the cruise, we had periods of daylight. There was a harsh beauty in the arctic landscape. The air was remarkably clean and very dry. Even from 60 miles, the peaks of Greenland’s mountains and glaciers looked like you could almost reach out and touch them. Occasionally, we would cross paths with polar bears. One evening, a mother and her two cubs provided some welcome diversion. They had quite an act… you would have thought they came from a circus the way they performed as the crew showered them with fruit, bread and other food. Another time, (I can’t recall if it was night or day – it was certainly dark!) our path was blocked by a rather larger polar bear in a deep sleep. Bright floodlights had no affect. The crew yelled, stomped and made all kinds of racket. Still, the bear slept on. The sharp crack of a rifle fired in the air netted only a slight ear twitch. Finally, the ear-splitting blast from the ship’s horn roused the sullen beast. Clearly unhappy, but not the least bit afraid, he plowed his way slowly through the snow. Several times he paused, glared back at us and voiced his considerable disgust at having his nap interrupted.

Polar bears were not the only diversion provided by nature. We were fortunate to witness several displays of the Aurora Borealis before proceeding too far north of the Arctic Circle. The shimmering lights with their shifting color hues were spectacular. Their silent beauty far exceeded any fireworks show man could devise!

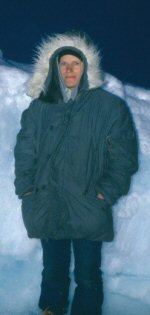

Ice LibertyOne of the highlights of the cruise occurred toward the middle of October. The captain decided to give the crew “ice liberty” before all daylight was lost. It was a warm arctic “day” (about 18oF) as we clambered down the ship’s ladder to set foot on solid ice. We were at about 77oN latitude. Here the ice was 10 to 15 feet thick – much of it having spent years circling with the currents around the Arctic Ocean to eventually flow out and south along the coast of Greenland. We were free to wander around (within limits, of course). The “polar bear watch” was stationed high aloft on the ship’s bridge wings armed with high-powered rifles. Having run across some bear tracks in the snow, I was glad they were there! There were some attempts at snowball fights, but the dry arctic snow didn’t pack very well. In every crowd, there’s always a die-hard golfer. Several of this hardy breed teed up on a makeshift course and aimed for the “green” outlined in orange paint. Do you lose a stroke when you ball disappears into an ice crevasse? There was also a little poetic justice. The Executive Officer had lectured endlessly to the crew about safety and issued a stern warning to stay well clear of the ship (the area broken up by the icebreaker refreezes quickly, but remains perilously thin). Yes, you guessed it, the XO managed to fall through the ice doing exactly what he’d warned everyone not to do. Fortunately, rescue divers were on standby for just such an accident and pulled him to safety. Rather chilled, but perhaps warmed somewhat by his embarrassment, the XO was forced to endure endless kidding for the remainder of the cruise.

Last FlightOne “day”, I donned a bright orange arctic survival suit (referred to by the crew as a “poopy” suit – don’t ask me why!), boarded the ships helicopter and lifted off in route to even more remote reaches of the ice pack. After an hour or so of flying in the blinding mid-day twilight, we circled our target. As we hovered over a large ice fissure, I lowered our portable CTD through this convenience opening to obtain yet another profile of the cold arctic waters. This time, there was no powered winch. Instead, I grabbed the handles on either side of the cable drum and cranked for all I was worth. The instrument package weighed only a few pounds, but dangling below the surface at the end of a couple of hundred meters of cable, it felt like the proverbial ton-of-bricks! Much of the challenge was to manage to maintain a steady pace not only while the probe descended into the depths, but also during its vastly more difficult ascent. Sweat from every pore in my body was trapped with me inside the poopy suit and soon pooled around my feet. I could no longer feel my arms by the time the CTD was finally safely back inside the helo,

With the “winch” out of commission, another cast was out of the question. Fortunately, our on-station time was exhausted as well, and it was time to find our way back to the ship. It was only then that I realized how crazy this whole operation was! With darkness rapidly approaching, we were miles and miles from even the remotest civilization – and in the ship’s only helicopter! What if we went down? It would take two or three days for the Northwind to battle its way through the multi-year ice to reach us, IF it could make it at all. The air base at Thule, Greenland would be the only real hope of rescue. And then, I couldn’t help but think about those bear tracks… Needless to say, all concern instantly evaporated as we lightly touched down on the ship’s flight deck. Mission accomplished (and I could even move my arms again)!

Shortly after our return, we learned that this would be the last flight of the cruise. The Coast Guard has grounded this class helicopter while we were out on our adventure. A crash back in the States revealed a potential problem with the rotor heads. It seems there was a defect that could allow the heads to break apart – without blades, a helicopter does not stay airborne long!

The Hull Ruptures!Early in November, we were again reminded that exploration in the arctic carries plenty of risk. Working against a particularly dense area of the ice pack, the Northwind’s hull suddenly ruptured and the frigid arctic water poured into the ship. Damage control crews sprang into action and quickly stopped the flow of the rapidly rising water. The 30-inch breach had occurred below the waterline abaft the bow on the port side where the ship’s armored hull thinned to about 1-½ inches.

We were stuck. Any attempt to move would run a high risk of further damage to the wounded ship. A ship at sea (or in the ice) must be largely self-sufficient. There is no one to call for help in the remote reaches of the arctic. The engineers pondered the problem and soon developed a plan to get us back in business. Pumping fuel and ballast into the starboard tanks, they were able to list the ship over 15 degrees and raise the damaged area clear of the water and ice. Skilled welders then worked for nearly three straight days to make the repairs. When they finished, the ship was as good as new with only a slight scar to attest for her trials.

Now we faced a new problem. After three motionless days, the ice had reformed around the ship and sealed the recently broken channel. It wouldn’t be the first time that an ice breaker became locked in ice and was forced to wait out the harsh winter months for the spring thaw. In her 40-plus years of service, the Northwind had never suffered that embarrassment, and if the crew had their way, it wouldn’t happen this time. Going forward was out of the question. The steady winds and currents were forcing the ice pack on us with tremendous force. The only hope was to get the ship turned around and break through the much thinner ice in our old channel. The ship churned, shuddered and struggled for hours. Slowly, but relentlessly, the ship formed a large basin and began to twist around. After almost 24-hours, we were finally free of the ice pack’s clutches – we had managed to travel about 100 yards back the way we had come!

Frozen FingersLate in the cruise, weather conditions had continued to deteriorate. Gale force winds were the norm with temperatures registering well below zero. On one particularly harsh day (night?), we had scheduled a special, 24-hour “in-situ” test near our most northerly penetration of the ice (around 79oN latitude). This sounded simple enough. All we had to do was lower a special array of instruments attached at intervals along a data cable. The array would remain in place for 24-hours, providing a continuous profile of the ocean’s thermal and saline structure at that one location. There was one little trick… we had to use our bare hands to tie the array to the ship’s oceanographic winch cable using short pieces of line! With winds gusting to 70kts and the temperature at around 26oF BELOW zero, the wind-chill was off the chart. Frostbite would occur in minutes and was an extreme risk. Undeterred, our hardy team bravely stepped out into the howling winds and began our work. As the array descended into the depths, each person took a turn, working quickly to make one knot and then retiring to the back of the line. The intervening moments were far too short to fully warm our hands before another turn. Each knot took longer than the last as our hands became clumsy from the numbing cold. At last, the task was done and we hurried back into the womb of the ship to thaw our frozen fingers.

Homeward BoundNovember 14th — at long last the day came for the Northwind to break free of the ice pack and set course south for Scotland. Our spirits were never higher in spite of the unforgiving arctic storm which seemed to seek vengeance on us for daring to enter the frozen domain. Battered and bruised, we finally emerged from the storm’s gauntlet and welcomed the first dim rays of daylight we had seen in weeks! The seas were calm as we passed the along emerald green coasts of the Hebrides islands and entered the Firth of Clyde. Weariness from our journey disappeared as we arrived at Her Majesty’s submarine base in Faslane, Scotland on what under other circumstances would have been a cold, dreary day. Wasting little time on goodbyes, Dr. Bourke and I clambered down the ladder and hailed a waiting taxi. Rushing past the castles and other sights of ancient Glasgow, we were focused on nothing but getting home.

For Dr. Bourke, home was only hours away. He had been living in Cambridge for several months while on a year’s sabbatical to occupy the University’s Arctic Chair. As the train pulled into the station, Dr. Bourke was happily greeted by his family. As for me, I was content to share their flat for the night and for the first time in weeks, enjoy sleeping in a bed that wasn’t moving! The sun shone brightly the next morning as I took a quick tour of this quaint English town before boarding the train for London and Heathrow. Settling in for the long ten-hour flight to San Francisco, I realized that the flight path was taking us across Greenland and much of the region we had explored for the past seven weeks. By day’s end, I would be home and the adventure would be officially over. A lot of work lay ahead compiling and analyzing the mountain of data we had collected. But just then, I could reflect on the memories of this very special experience with the satisfaction of knowing that I was now a veteran arctic explorer.